Blogs

The Reunion Band

Here is a rare occasion for me to share information on a bluegrass band that has an African American Member. It is The Reunion Band out of Boston. Here is the info from their home page reunionbluegrass.com. Their "token" African American member in Richard Brown who plays mandolin.

Known for its tight vocal harmonies and solid traditional bluegrass sound, the Reunion Band features veteran Boston-area musicians Richard Brown (mandolin), Dave Dillon (rhythm guitar), Margaret Gerteis (acoustic bass), Laura Orshaw (fiddle) and most recently BB Bowness (banjo) . The band, which has been around since 2002, takes its name from the fact that its members have played together off and on and in various configurations for over 30 years.

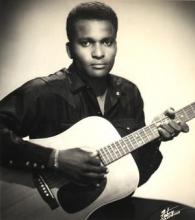

Charley Pride's Big, Black, Country Cojones

Twang Is Not a Color

African-American Presence in Country Music History

Charley Pride - an Anomaly

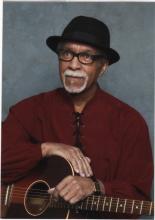

Brent Williams inducted into the Nova Scotia Country Music Hall of Fame

Brent Williams

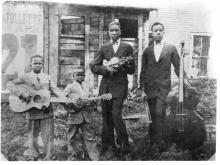

Rural Black String Band Music by Charles Wolfe

The first time I think I ever seen Arnold Schultz … this square dance was at Rosine, Kentucky, and Arnold and two more colored fellows come up there and played for the dance. They had a guitar, banjo, and fiddle. Arnold played the guitar but he could play the fiddle-numbers like "Sally Goodin." People loved Arnold so well all through Kentucky there; if he was playing a guitar they'd go gang up around him till he would get tired and then maybe he'd go catch a train …. I admired him that much that I never forgot a lot of the things he would say. There's things in my music, you know, that comes from Arnold Schultz-runs that I use in a lot of my music (Bill Monroe, quoted in Rooney 1971).1

Quotes such as this one from bluegrass star Bill Monroe are by no means atypical. For ten years I have been interviewing at length older country musicians and folk musicians from the 1920s and 1930s about that misty borderland wherein traditional American folk music was somehow transformed into commercial country music; many, many of them mention bands such as Arnold Schultz's string band, point to them as influences, as models, as colleagues. They point to a genre of American music that most scholars have ignored and that most members of the general public do not even know existed: a genre that DeFord Bailey, the famous harmonica player on the early Grand Ole Opry, defined for me as "black hillbilly music." "Sure," he said, "black hillbilly music. Everybody around me grew up playin' that. Fiddles and banjos and guitars; they weren't playin' no blues then. It was black hillbilly music" (Bailey 1975).

For years the emphasis of those studying black American folk music has been directed to religious music (the first really respectable music to study), to jazz (the first commercially successful brand of music), or to blues. Yet do these three forms really account for all of the rich variety of black music found in folk tradition-or just the most visible ones? What about the rural fife-and-drum tradition, which has lingered unnoticed in Tennessee until this present generation? What about the tradition of black non-blues secular song? And what about the tradition of the rural string band music? To explore these aspects of black music requires a great deal more digging and musical archaeology but might yield in the end results as fruitful as those coming from jazz, blues, and religious music studies.

1. Arnold Shultz, incidentally, went on to influence Kennedy Jones, who taught white musician Mose Rager, who taught Merle Travis and Chet Atkins.

DISCOGRAPHY

Virginia Traditions. BRI-001. Blue Ridge Institute, Ferrum College, Ferrum, Va. Blind James Campbell and his Nashville Street Band. Arhoolie 1015, recorded as recently as 1962. Altamont: Black string band music from the Library of Congress. Rounder Records or Compact Disc 0238. 0942-1946 recordings by the John Lusk String Band and the fiddle-banjo duo of Nathan Frazier and Frank Patterson, with extensive annotation by the author.}

Originally published in Black Music Research Newsletter 4, no. 2 (Fall 1980). Used by permission of Mary Dean Wolfe.